In Conversation with Mitch Erzinger, the Archivist of Elizabeth Taylor’s Estate

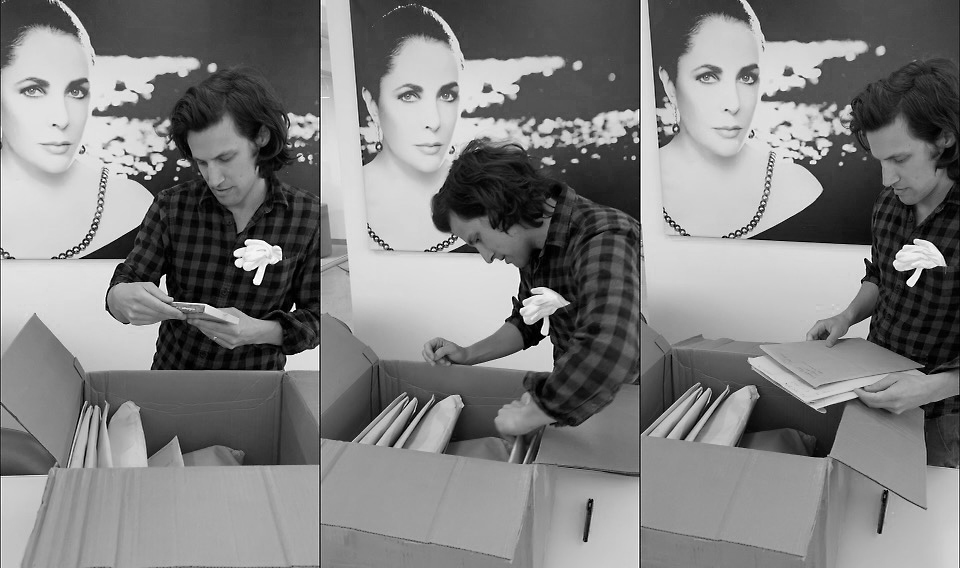

From her grade school assignments to correspondences with her parents, to her famous wardrobe and collection of personal effects, every item is identified and cataloged by Mitch Erzinger, the Archivist for the Elizabeth Taylor Estate. We sat down with Mitch to learn more about what it means to archive all of the papers and beautiful objects from Elizabeth’s life.

Q: What does it mean to be an archivist for someone's estate?

A: It means preserving and organizing the contents of the estate so that it's protected and also rendered accessible in some way to those from the outside— researchers or even if it's just the family or the trust or whoever. Given that it's a trust, it's a private institution. So it's set up according to the rules of the trust. But that's generally the gist of it: the focus is on preservation and access, making things “find-able” so that we know what's there and we know how to get to it. An archivist doesn't necessarily tell a story, but they facilitate storytelling.

Q: Can you describe a typical day?

A: A lot of what I do is physical, less of it now because we've processed so much of the material, but there are still a lot of papers, for example, to be organized that we have in a separate warehouse that I haven't even gone through yet. So, I might go through material and select items that we identify as being particularly valuable from either a content or historical perspective, then I’ll digitize material and catalog it in our database, and work on physically housing material. So if it's, for example, a photograph, I will scan the photograph and I'll catalog it to create a record for it, inputting information like the photographer, the artist's name, giving it a title, description, and then these various pieces of metadata, like what is the year? What is the media? Then I’ll note where it is physically located, which box, and then which folder in the box.

I also do some light preservation work. We keep photographs in archival plastic sleeves, we use all acid-free paper and folders and boxes to protect the material, and we have a climate-controlled room where we keep most of the material. Then the rest of the time is made up of fulfilling requests, mostly internal up to this point. But now we do have outside partners that are utilizing the archive. We will give them a certain level of access, where they can look at our database and then request material. I’ll retrieve and deliver that material, or do some research to see if we have a certain type of document in the archive.

Q: Did you personally invent the organization system for archiving?

A: Charlie Scheips, the founding director of the Conde Nast Archive, was initially the project director and set up the framework in early 2015, bringing in myself and another colleague, Jennifer Vanoni, as freelance archivists several months later to work on cataloging and digitizing the photograph collection, which was the primary focus then. Together we expanded and refined the organization scheme as the project grew. After Charlie left in 2016, I suggested that they establish a permanent archivist position to continue the project. Since then, I've been the primary archivist and I expanded the existing organization scheme of metadata and refined it. Some of the things that I saw needed to be changed or altered a little bit, because at first we were just focused on the photographs, and then we slowly started getting into the papers as well.

When I say papers, I mean, any kind of documents. A lot of it is correspondence. We also have legal records. We have office memorandums, press releases, drafts and copies of speeches, tax records—all of that. It really runs the gamut.

As an archivist, you need to find the balance of maintaining conventions, like using certain vocabularies or organization schemes. Looking towards the future, one day this will become public, either through the trust as its own archive, or this collection will join another archive, so you want it to be able to coexist within that. Even if you go to our website, we have very brief but specific language on the archive page that speaks to the fact that we are also still building out the archives. So, we are in the business of accepting donations and contributions to the archive that people may have.

Q: What kinds of items do you receive?

A: A couple of years ago we had somebody come in who gave us one of Elizabeth's physiology tests from the MGM school; I think it was from 1948. It was a couple of handwritten pages, which was so cool. The woman who donated it to us was part of some teacher’s union; I don't know how this document ended up there, but she came to us with it.

Q: What grade did she get?

A: I want to say B+. Good job, Elizabeth. We’ve also received some clothing items, a few pieces of correspondence...Elizabeth lived a long, full, international life, and it’s possible that old files and letters are out there in attics, basements, storage facilities, etc., and we hope that the more people know that there is in fact an Elizabeth Taylor Archive, an official place dedicated to preserving her history and legacy through documentary evidence, that people who may not otherwise know what to do with some of the things they have now have a place to send their items, where they will be preserved as part of Elizabeth’s history.

Q: Let's talk about your background and how you came into this role. How does someone become an archivist?

A: I started when I was doing my undergraduate at UCLA. I started working in their library of special collections, which is an environment that has restricted access. Anybody can walk in, but you have to register and request material from their database and they bring it to you in a special reading room where you look at things either with gloves, or one folder at a time. I really enjoyed that environment and when I graduated, I got a temporary job as a processing archivist at the Getty Research Institute, where I was working on architectural records. I decided that it was something I wanted to pursue potentially as a career, and so I returned to school at UCLA for a master's degree in Library and Information Studies. Then I answered an ad that was looking for a freelance photo archivist for a recently deceased Hollywood icon and got the job, and found out it was Elizabeth Taylor.

Q: How would you say it's different working for an individual’s trust versus a larger institution?

A: For one, we're very small. In a larger institution, the duty is towards the public. There are larger departments and there are very specific sets of standards that you are working within. And you have a lot of more material, so you’re working on multiple collections, whereas working for the trust, I'm all in on Elizabeth.

Q: What’s the most interesting discovery you've made over the past five or six years working at the trust?

A: It's hard to pick one because there are so many. Some of the things that I find the most fascinating are what we have from Elizabeth's younger years, which we have thanks to her mother, who kept so much. We have things like little scraps of paper with her drawings from when she was a little girl...seven, eight-years-old. We have little notes that she wrote to her parents or to her brother. We also have essays that she wrote when she was a teenager at school, these handwritten essays with notes, and some are graded. You get to read these things before she was really famous and before she was a star, and you see how she was very much the same person. She always had this sense of love for people and a caring personality, and also very courageous and rambunctious.

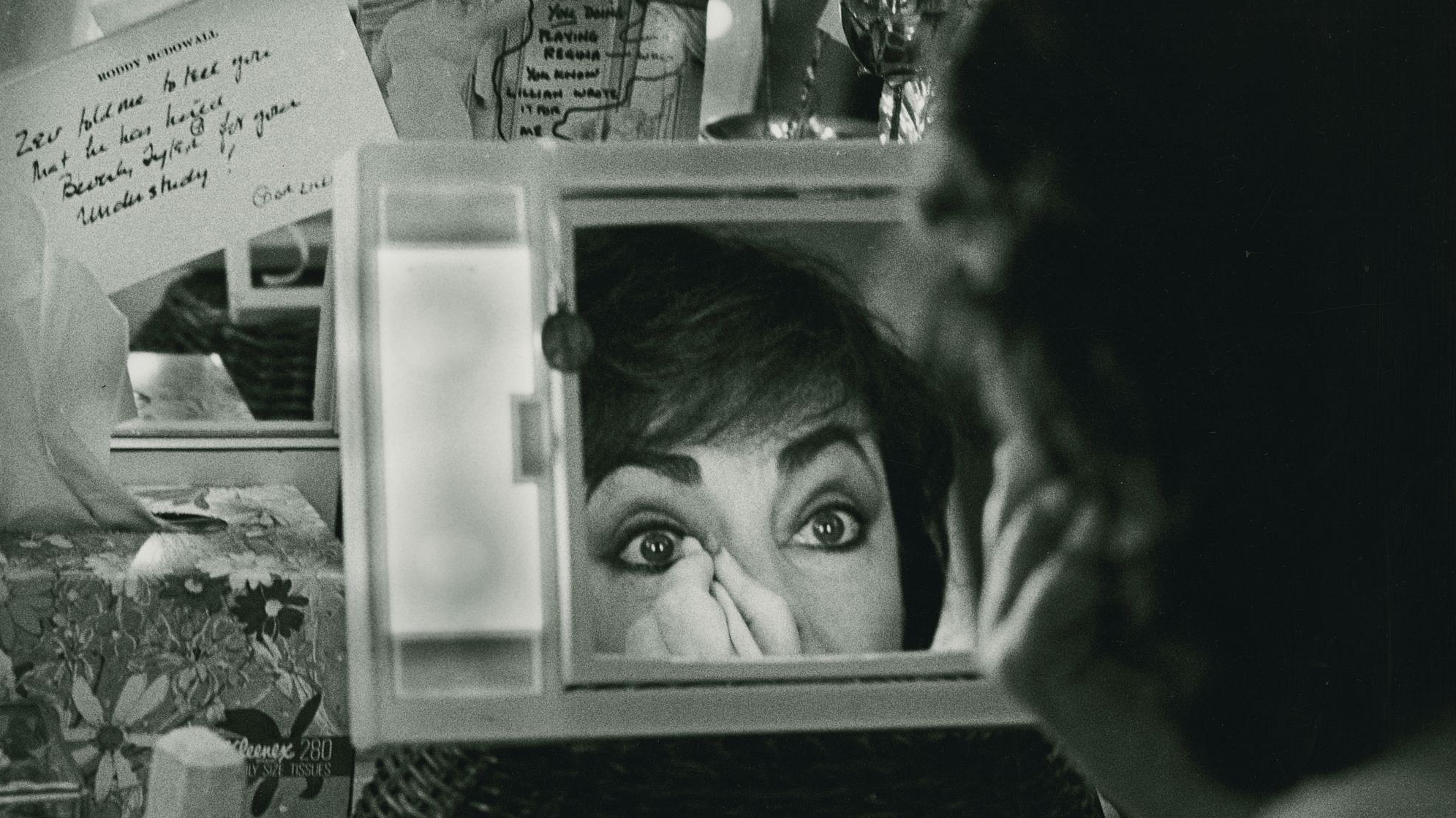

We also have a great series of black and white photographs that she took herself in the late sixties. I think she and Richard Burton were in London. They are a series of portraits of the people who were around them at the time, some recognizable actors, other people in the industry, and they were all stamped with her name on the back.

Q: What would you say is the most challenging part of your job?

A: The most challenging part is holding back and knowing that we can't make everything public for the world. The archivist in me wants to make things accessible, but there's a whole other aspect involved. Also, there is a period from mainly the 1950s to the early 1960s where we really don't have any documentation, so that's been frustrating and a challenge to try and figure out what happened. She would have been in her twenties; she was working a lot and was married multiple times. We have photographs but very little in the way of documentation, so it’s a mystery.

Q: What personality traits would you say make for a good archivist?

A: I guess those who tend to be slightly more introverted because there's a tendency to work alone. Thankfully, at our offices, there's a lot of light, but generally, they tend to be in kind of dark basements with lots of paper and old books.

Q: Have you learned anything new about Elizabeth that might surprise her fans?

A: It's hard for me to say because I knew who she was before I got this job, but I didn't know her as in-depth as some of her ardent fans do. I always think to myself, I got lucky that it's Elizabeth Taylor—besides being a movie star she was a good person who did a lot of good in the world; she is inspirational. She's multi-dimensional, colorful and entertaining. I think in all the papers, it’s obvious that she was just a very caring person.